So much information has been devoted to the subject of roof venting that it’s easy to become confused and to lose focus. So We’ll start by saying something that might sound controversial, but really isn’t: A vented attic, where insulation is placed on an air-sealed attic floor, is one of the most underappreciated building assemblies that we have in the history of building science. It’s hard to screw up this approach. A vented attic works in hot climates, mixed climates, and cold climates. It works in the Arctic and in the Amazon. It works, absolutely everywhere—when, executed properly.

Unfortunately, we manage to screw it up again and again, and a poorly constructed attic or roof assembly can lead to excessive energy losses, ice dams, mold, rot, and lots of unnecessary homeowner angst. Here, I’ll explain how to construct a vented attic properly. We’ll also explain when it makes sense to move the thermal, moisture, and air-control layers to the roof plane, and how to detail vented and unvented roofs correctly

Theory behind venting

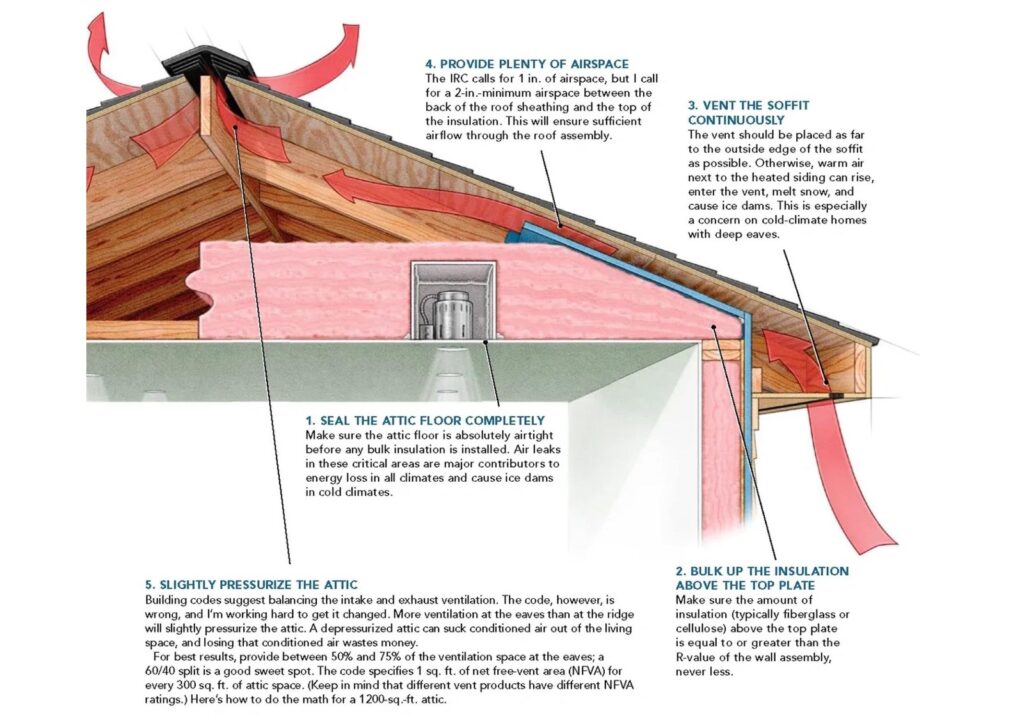

The intent of roof venting varies depending on climate, but it is the same if you’re venting the entire attic or if you’re venting only the roof deck. In a cold climate, the primary purpose of ventilation is to maintain a cold roof temperature to avoid ice dams created by melting snow and to vent any moisture that moves from the conditioned living space to the attic. In a hot climate, the primary purpose of ventilation is to expel solar-heated hot air from the attic or roof to reduce the building’s cooling load and to relieve the strain on air-conditioning systems. In mixed climates, ventilation serves either role, depending on the season.

Vent the attic

A key benefit of venting the attic is that the approach is the same regardless of how creative your architect got with the roof. Because the roof isn’t in play here, it doesn’t matter how many hips, valleys, dormers, or gables there are.

It’s also important to ensure that there isn’t anything in the attic except lots of insulation and air—not the Christmas decorations, not the tuxedo you wore on your wedding day, nothing. Attic space can be used for storage, but only if you build an elevated platform above the insulation. Otherwise, the insulation gets compressed or kicked around, which diminishes its R value. Also, attic-access hatches are notoriously leaky. You can build an airtight entry to the attic, but you should know that the more it is used, the leakier it gets. How do people get this simple approach wrong? They don’t follow the rules. They punch a bunch of holes in the ceiling, they fill the holes with recessed lights that leak air, and they stuff mechanical systems with air handlers and a serpentine array of ductwork in the attic. The air leakage from these holes and systems is a major cause of ice dams in cold climates and a major cause of humidity problems in hot climates. It’s also an unbelievable energy waste no matter where you live. Don’t think you can get away with putting ductwork in an unconditioned attic just because you sealed and insulated it. Duct sealing is faith-based work. You can only hope you’re doing a good-enough job. Even when you’re really diligent about air sealing, you can take a system with 20% leakage and bring it down to maybe 5% leakage, and that’s still not good enough. With regard to recessed lights and other ceiling penetrations, it would be great if we could rely on the builder to air-seal all these areas. Unfortunately, we can’t be sure the builder will air-seal well or even air-seal at all. So we have to take some of the responsibility out of the builder’s hands and think of other options. In a situation where mechanical systems or ductwork has to be in the attic space or when there are lots of penetrations in the ceiling below the attic, it’s best to bring the entire attic area inside the thermal envelope. This way, it’s not as big a deal if the ceiling leaks air or if the ducts are leaky and uninsulated.